Cameroon crisis threatens Cross River Gorillas as displaced people flee to protected areas

Many displaced by the conflict are fleeing to biodiversity hotspots, clearing forests to build homes and hunting endangered animals for survival.

Around midday in the lush bushlands of western Cameroon, Nsong Gabriel enters a small makeshift hut to get a cup of the local brew. He carries his old rifle in one arm and drags along his rewards from his hunt with the other: a porcupine, caught in a trap he laid the previous day, and two monkeys.

He complains that this has been a relatively unproductive expedition. “Most often, I get alligators, porcupines, monkeys, antelopes, snakes and bush swine,” he says. But it is at least something, and he will be able to trade the animals for essentials.

“I exchange them for a bit of cash and basic items like maggi, salt and rice brought in by those who come here to buy bush meat,” he explains.

Gabriel wasn’t always a hunter. Until recently, he was a primary school teacher, but then the unrest in Cameroon’s two Anglophone regions began. The turmoil started as low-level protests in the North West and South West regions over perceptions that the central Francophone-dominated government was discriminating against English-speakers. But it quickly spiralled into a full-blown crisis. The government clamped down violently on activists. Armed separatists calling for a new state of Ambazonia emerged. And both separatists and security forces are now engaging in deadly attacks, with villagers often caught in the mix.

Like many others, Gabriel’s life turned upside down and he was forced to flee his home. According to UN estimates, he was one of around 160,000 to face the same fate. Many resettled in nearby national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and forest reserves.

“More than half of these people have invaded and remained in these habitats,” says Kari Jackson Bongnda, Executive Director of Sustainable Run for Development (SURUDEV).

Gabriel was one of them and, with survival his priority, he soon turned to hunting bush meat. Most of the animals he kills are protected under Cameroonian law, but he is rarely short of buyers given how the conflict has made the trade of several other foods more difficult. Road blocks by the so-called Amba Boys have interrupted the transport of imported frozen fish from the port city of Douala. Cattle rustling along major highways has scared breeders from bringing their stocks to market. And the uncertainty in the region has made it difficult to domesticate chickens, goats and pigs locally.

Many people have had to turn to bush meat both to eat and to earn an income. According to environmental specialists, this has made endangered species highly vulnerable.

“The result, which would be devastating to conservation, would be migration of wildlife to safer habitats, which might not necessarily be their niches, resulting in consequent extinction,” says Kari Jackson.

The situation is so critical that Louis Nkembi, founder of the local NGO Environmental and Rural Development Foundation (ERuDeF), believes the government should declare an ecological emergency. “In the Lebialem highlands, elephants have been liable to poaching. Now with the crisis, the activity has skyrocketed,” he says. “Endemic endangered apes of Cameroon, especially gorillas and monkeys too are being decimated.”

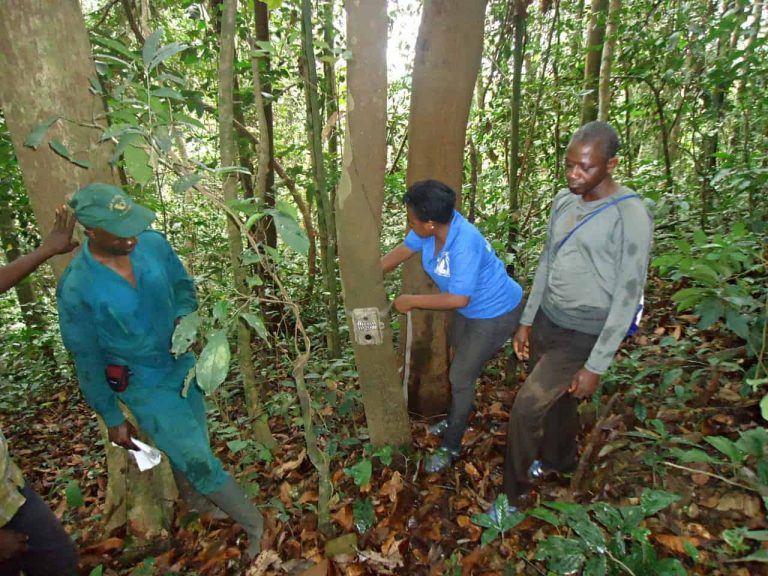

Ordinarily, these unique environmental areas would be guarded, but rangers have been forced to flee in turn. A Divisional Delegate of the Forestry and Wildlife ministry confirmed that most had deserted the area in the last month.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, one former eco-guard at Bakossi National Park described how unknown gunmen had assaulted him, leaving him injured, before ordering him to vacate his post. “I barely survived, thanks to God,” he said.

Another ranger claimed a group of displaced people threatened him into leaving too. “I had to run for my dear life,” he confessed. “I couldn’t stake my life to protect that of an animal.”

Clearing the forest

As well as endangering Cameroon’s protected species, the movement of people fleeing the conflict has also resulted to deforestation and damage to biodiversity hotspots. In parts of the Bakundu Forest Reserve, for instance, significant sections of trees have been cut down to make space for new villages and to be used as construction materials and fuel.

“The displaced persons have been left at the mercy of their new environment and will do just anything for survival, irrespective of the long-term consequences,” says Tabangmua Danisius, Director of Forestry and Environment Conservation Society (FOECONS). “In some areas we have visited, people are using chemicals like gamalin to fish in their quest to get protein.”

Describing the situation as “catastrophic”, he warns that human activity is contaminating land and water, contributing to soil erosion, and destroying the habitats needed for rare plants and animals to survive.

An employee at the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)’s Coastal Forest Programme, echoed these concerns. “The already dicey environmental situation in the troubled area is now worrisome,” they said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

As part of the Bonn Challenge initiative, Cameroon pledged to reinstate more than 12 million hectares of deforested and degraded land by 2030. Experts celebrated this was the biggest commitment made in the species-rich Congo Basin, home to the world’s second-largest tropical rain forest. However, this lofty vision looks like it will be thwarted by the continuous pressure on ecosystems as Cameroon’s crisis rages on with no end in sight.

This could damage Cameroon’s rich and unique environment irreversibly. But for the thousands of people uprooted by the conflict and forced to run from their homes, there are few alternatives when the priority is simply survival until the conflict abates.

“All I do is hunting. Early in the morning, I go out to check my traps which I must have set by evening the previous day. Late in the night, I move out with my gun and torchlight in search of game,” says Gabriel. “I don’t have any other thing I do here besides hunting.”

This article was originally published by African Arguments on 12 July 2018 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.