Species profile

Rarest of All Apes

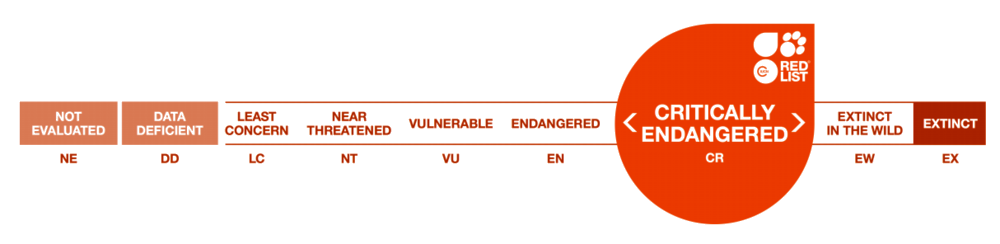

The Cross River Gorilla is the most endangered of all gorilla subspecies, with fewer than 300 individuals estimated in the wild and, until 2016, only one known in captivity. It is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN—the highest threat category for species still surviving in the wild.

This status indicates that the population has declined, or is projected to decline, by at least 80% over three generations. The species’ critically endangered classification reflects the fragmentation of its habitat, ongoing hunting pressure, and the very small population size.

According to the IUCN, the Cross River Gorilla is also one of the 25 most endangered primates worldwide, underscoring its urgent need for protection.

Importance of the Cross River Gorilla

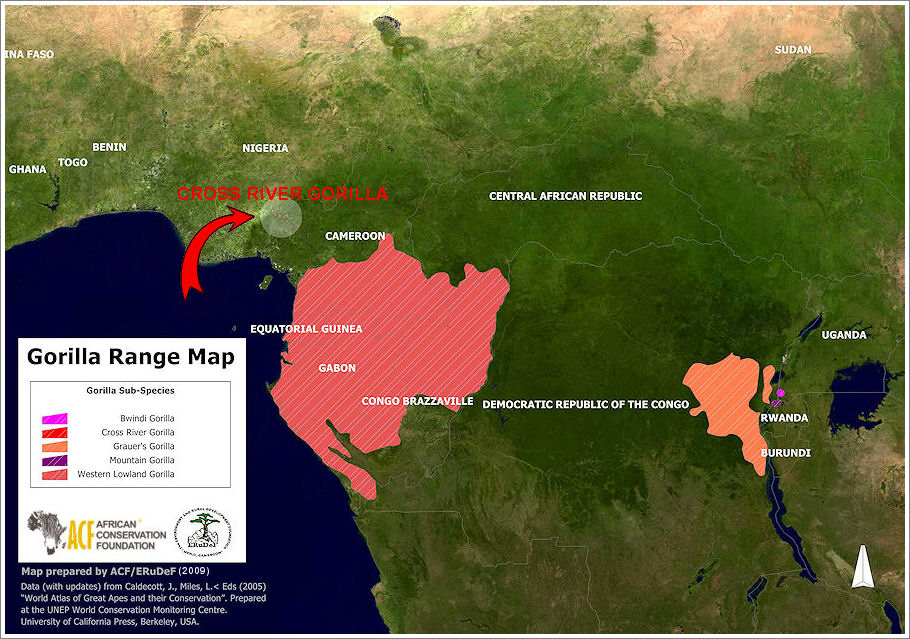

The Cross River Gorilla is a unique subspecies found only in a small, fragmented region of Nigeria and Cameroon. With just a few hundred individuals remaining, it faces a real risk of extinction without effective conservation and protection.

The Cross River region is recognised as a biodiversity hotspot—an area with exceptionally high species richness and endemism, spanning taxa such as amphibians, butterflies, fish, and small mammals. According to Conservation International, there are 34 such hotspots worldwide, covering just 2.3% of the Earth’s land surface, yet supporting more than 50% of terrestrial plant and animal biodiversity, including all 25 of the most endangered primates.

This hotspot is home to numerous primates and other endemic species beyond the Cross River Gorilla, including the Nigeria-Cameroon Chimpanzee, Preuss’s Gibbon, forest elephants, forest buffalo, and several species of duiker, as well as 26 bird species found nowhere else.

Several parts of the region have been designated by BirdLife International as Important Bird Areas, while USAID’s Central African Regional Program for the Environment has recognised it as a Landscape of High Conservation Priority. The region is also included in two of WWF’s Endangered Terrestrial Ecosystems, highlighting its global ecological significance.

Genetics

Recent genetic studies of Cross River gorilla populations suggest the situation is somewhat more hopeful than once feared — but also more precarious in important ways. Using non‑invasive sampling and, more recently, whole‑genome data from shed hairs, researchers have confirmed that the gorillas form three main subpopulations, with evidence of past gene flow between certain sites.

Although the overall genetic diversity of the subspecies is low compared to many great apes, heterozygosity (a measure of genetic variation) remains similar across the different subpopulations. However, the gorillas also bear long runs of homozygosity in their genomes — a genetic signature indicating recent inbreeding and a strong population bottleneck roughly 100–200 years ago.

This deeper genomic analysis refines earlier findings, revealing that genetic connectivity has existed between subpopulations — for example between the western Afi Mountain Sanctuary and the Mbe Mountains. Yet, much of this connectivity appears to have occurred historically; in the present day, many populations remain isolated or only tenuously connected.

That said, the pattern of occasional migration and mixed ancestry individuals is encouraging: it confirms that dispersal between habitat fragments was possible and successful in establishing new genetic links. This underlines the critical importance of preserving, restoring, and strengthening habitat connectivity across the gorillas’ range.

Finally, recent habitat‑modelling and remote‑sensing work suggests that the actual geographic range of the Cross River gorilla may be larger than previously assumed. Some corridors and forest linkages — though fragile — still connect many of the known localities, offering hope that further genetic exchange might still occur under the right conservation strategies.

Key takeaways for conservation

- The Cross River gorilla still suffers from small population size, fragmentation, and genetic bottlenecks.Genetic data show low diversity and signs of recent inbreeding.

- Historical connectivity was real — and genetic exchange occurred between subpopulations. This should guide conservation efforts toward protecting and restoring habitat corridors.

- Mixed‑ancestry individuals prove that migration was not only possible but reproductively successful.Restoring connectivity could help reduce future inbreeding risks.

- Given newly discovered potential habitat corridors and previously unconfirmed range extensions, the current geographic distribution may be broader than earlier maps indicated. This increases the hope but also underscores the urgency of protecting these fragile linkages.

Physical Traits

Studies of the limited skeleton and coat specimens available as of 2000 revealed a few distinguishing characteristics of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli). These gorillas tend to have shorter hands and feet than other western gorillas. Their thumbs are relatively short, resulting in a high opposability index, which may reflect adaptations for a more terrestrial lifestyle. Interestingly, females may be slightly larger than typical Western Lowland Gorilla females.

The skull and teeth of Cross River Gorillas show several unique traits. Males have a smaller gape, and their cheek teeth have a reduced surface area, suggesting they consume smaller, harder, or more abrasive food items than Western Lowland Gorillas. The shape and heavy wear of the incisors indicate that front teeth play a particularly important role in feeding, potentially for biting tougher vegetation or foods that require less chewing. Many skull features also suggest stronger chewing forces, although Cross River Gorillas may spend less time processing food compared to other gorillas.

The combination of shorter hands and feet and the skeletal characteristics of the skull suggest a more terrestrial lifestyle, consistent with adaptations seen in primates inhabiting less dense or more open habitats. Some of these traits may also reflect responses to lower fruit abundance in their environment.

Evolution and Pleistocene Forest Refuges

Cross River Gorillas likely diverged from other western gorillas during the Pleistocene, when dry phases reduced arboreal food sources and favored terrestrial herbivory. The Cross River region may have acted as a forest refuge, allowing the subspecies to evolve in isolation from other gorilla populations. Later dispersal was probably limited by ecological specialization and geographical barriers, such as the Sanaga River, contributing to the high number of endemic species and subspecies in the region.

It is important to note that the current habitat may not reflect the environment in which the Cross River Gorilla evolved. Montane forests on the Obudu Plateau and Bamenda Highlands once provided unique habitats that have largely been converted to grassland, potentially shaping the adaptations observed today.

Differences from Other Gorillas

Cross River Gorillas are distinguished from Western Lowland Gorillas by:

- Lower cheek tooth surface area

- Smaller cranial vault volume

- Narrower incisor rows and palate width

- Narrower glenoid diameters

Male Cross River Gorillas also exhibit shorter facial length and palate lengths compared to male Western Lowland Gorillas. While not all skulls will show every feature, a combination of these traits reliably identifies Gorilla gorilla diehli.

Dental morphology is generally more genetically constrained than skeletal morphology, suggesting that the distinctive teeth of Cross River Gorillas reflect genetic differences, rather than environmental variation. Interestingly, comparisons between Mountain and Eastern Lowland Gorillas show little dental differentiation, highlighting the genetic distinctiveness of the two western gorilla subspecies.