Conservation Threats

Bushmeat Trade

In many forest-adjacent communities, bushmeat provides the main source of animal protein—reaching up to 84% in some Nigerian villages. Demand is widespread, and many people prefer bushmeat over domestic livestock. In a few remote settlements, it remains the only accessible form of animal protein.

The bushmeat trade operates through a chain: hunters and trappers sell their catch to middlemen, who transport it—often over long distances—to markets far from the original hunting sites. This disconnect creates the false impression of an abundant supply, even when wildlife has already been depleted locally. Bushmeat is also frequently smuggled from Cameroon into Nigeria.

Buyers travel significant distances to these markets, and bushmeat is additionally sold in restaurants, hotels, and along roadsides. To evade detection, much of the trade occurs early in the morning, on weekends, or during holidays, and is often moved along unofficial back routes. While these clandestine practices suggest that enforcement measures are having some effect, the trade persists.

Some species are also sold for ritual or fetish purposes, as souvenirs, or—even when captured alive—as pets. Gorilla skulls have traditionally been kept as trophies.

Measures that could curb the bushmeat trade include:

- strengthening law enforcement and ranger capacity,

- improving equipment and paramilitary training for protected area staff,

- clarifying protected area boundaries,

- expanding education on conservation and wildlife laws,

- providing accessible protein alternatives, and

- supporting domestication of suitable forest species for communities that prefer the taste of wild meat.

Impact on Cross River Gorillas

The illegal capture of young gorillas for the pet trade remains a serious threat. To obtain an infant, hunters often kill several group members, including the mother—yet the young usually die as well due to the specialised care they require. Only one confirmed Cross River Gorilla is known to be in captivity, rescued from a trader and now housed at the Limbe Wildlife Centre in Cameroon. Increased education and government-level advocacy are beginning to reduce this trade.

Limited educational opportunities in rural areas mean many young people spend their days hunting, trapping, fishing, or gathering forest products instead of attending school. Entire families also clear new farmland—usually for subsistence crops—leaving little time or capacity for conservation awareness.

Although no epidemic diseases have been recorded in Cross River Gorillas, any infectious agent—such as anthrax or Ebola—could devastate this small, fragmented population, especially as people and livestock move closer to gorilla habitats.

The transboundary nature of the Cross River Gorilla’s range, spanning Nigeria and Cameroon, presents additional organisational and legal challenges. Wildlife, of course, does not recognise borders. One gorilla group ranges on both sides of the boundary between Takamanda and Cross River National Park. Encouragingly, cooperation between rangers led to the first joint survey in 2007, and the upgrade of Takamanda to a National Park has further improved protection for these border-crossing gorillas.

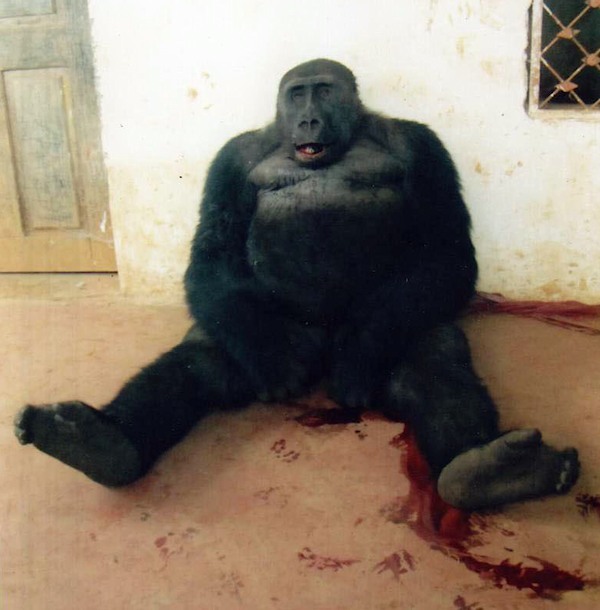

Gorilla Killings

Although the Cross River Gorilla is legally protected throughout its range, isolated killings still occur—and in such small, fragmented populations, the loss of even one individual can be devastating. The death of a silverback, for example, often forces females to join another male, who may kill their infants in order to breed. Gorillas are targeted not only for bushmeat, but also for their bones (used in traditional medicine and fetishes), and infants captured alive may enter the illegal pet trade.

Documented Incidents

2014 — Lebialem Highlands, Cameroon

In March 2014, a male Cross River Gorilla was shot near Pinyin in the Santa Sub-Division of Northwest Cameroon. According to wildlife expert Neba Bedes of ERuDeF, the killing—ordered by the Chief of the Gendarmerie Brigade—was justified as “self-defense” without proper checks to assess any threat posed by the animal. More than 45 bullets were allegedly used, along with clubs and stones, leaving the elderly silverback dead in a pool of blood.

2006 — Bumaji, Nigeria

Two apes, possibly gorillas, were reported killed near the Okwangwo Division of Cross River National Park in late 2005. Witness accounts were unclear, and the animals may have been chimpanzees. The case was complicated by a long delay in reporting, the hunter’s retracted confession, community resistance, and tension that prompted Wildlife Conservation Society staff to withdraw for safety. Following the incident, a new ranger post was established and community rangers were recruited.

1998 — Afi Mountains, Nigeria

A well-known prolific hunter was arrested for killing a gorilla at the Afi site. Despite repeated efforts by Pandrillus to provide him with alternative employment over a 12-year period, he repeatedly returned to hunting. Authorities concluded that stronger action was necessary and arrested him.

1989 — Nigeria

Reports indicated that twice as many gorillas were being killed annually as were being born. At the time, a single gorilla carcass could fetch twice the average monthly wage.

1986 — Cross River Region

Fifteen communities were actively hunting within known gorilla range. One community alone reported killing eight gorillas.

Cultural Taboos

In some areas, traditional beliefs strongly discourage hunting gorillas. Among communities in Kagwene, Bechati-Fossimondi, and parts of the Obudu Plateau, gorilla meat is taboo—often because gorillas are believed to be closely related to humans, making consumption akin to cannibalism. Elsewhere, the sale of gorilla meat is prohibited: for example, Boki hunters must share any gorilla meat with all family members, making the burden of distribution a deterrent.

Conservation Measures

Our long-term conservation and monitoring programme, built on partnerships with local forest management committees, helps prevent gorilla killings. We train community members, support conflict mitigation in cases of “problem animals” together with government authorities, and maintain a continuous presence of researchers. Strengthened law enforcement and community engagement are steadily reducing threats to this critically endangered species.

Habitat Loss

Habitat loss and fragmentation—alongside hunting, disease, and the capture of infant gorillas for the pet trade—remain among the most serious threats to the Cross River Gorilla.

Historical records are sparse, but a 1957 report suggests that gorillas were once more common in this region, aligning with genetic evidence pointing to a recent population decline.

This landscape supports both Cross River Gorillas and a rapidly growing human population. Large portions of forest have been cleared for agriculture, pasture, and small- to large-scale logging. In the Bamenda Highlands, extensive grasslands are regularly burned, and accidental or intentional bushfires occur across the region, particularly during the dry season. These fires can spread quickly, degrading habitat and accelerating the conversion of forest to savannah.

Even without total forest loss, frequent disturbance pushes gorillas away from areas they would otherwise use. Logging operations, human encroachment, and persistent activity can make habitats unsuitable for these shy and wary animals.

Forest edges are being steadily eaten away, particularly around enclaved communities inside the Cross River and Takamanda National Parks. Continued expansion could bisect the Okwangwo division of Cross River National Park entirely. Outside core gorilla sites, unprotected forest corridors are degrading, threatening to isolate groups and block natural migration.

Poor road access has long been a challenge for residents, who struggle to move cash crops or reach medical care. Yet road development brings significant ecological costs. New and improved roads fragment habitat, act as barriers to wildlife, and open previously intact areas to logging, hunting, trapping, and increased extraction of non-timber forest products (NTFPs). Logging routes, in turn, become pathways for poachers, extending human pressure deeper into the heart of the forest.